You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

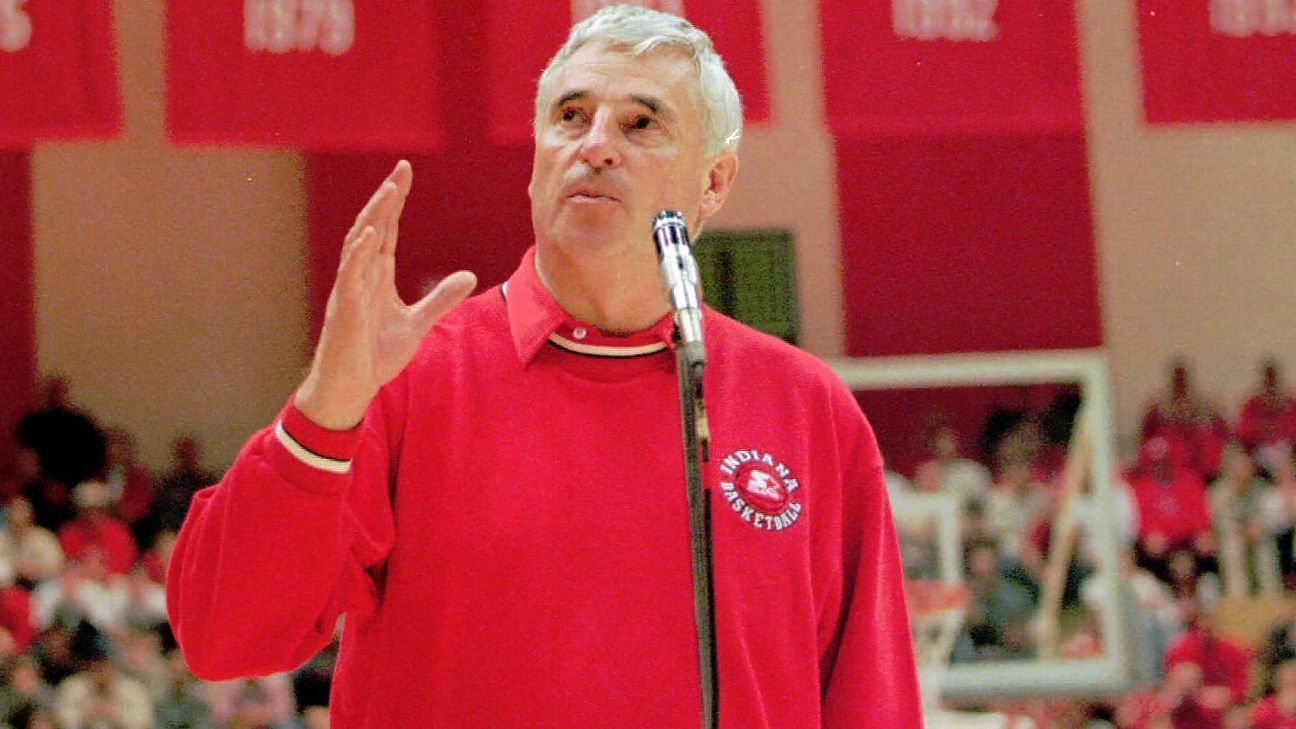

RIP Bob Knight

- Thread starter paultzman

- Start date

billthetruth

Well-known member

An all time great. RIP Coach Knight.

He would have not been as great in this snowflake era

He would have not been as great in this snowflake era

A few examples of him "breaking the reporters chops"

I thought coach Knight comported himself quite civilly in all of those exchanges.

If I didn't know better, I'd think he was bowling in those photos

In his words, from his book "Knight".:

I coached for eight seasons at West Point. In those years, I developed an interesting relationship with probably the three most prominent people in New York City basketball history—Clair Bee, Joe Lapchick, and Nat Holman.

When he retired in 1965, he was the most revered coach I had ever known, until I became acquainted with Henry Iba.

I took Coach Holman and Coach Bee to Mr. Lapchick’s wake. He had loaned me the scrapbook he had put together on the 1950s college basketball gambling scandal. He showed the scrapbook to every player who ever played for him after that happened. I gave it back to Mrs. Lapchick that night; several months later she sent it to me to keep. At the wake, she took me into a little side room and told me, “I know you didn’t play for Joe, but I want you to understand, you were one of his two favorites.” No comment ever meant more to me. And I never asked her about the other.

Every time one of my Army teams played in Madison Square Garden, when I would walk out on the floor I would look over to where he always sat. He’d put his thumb under his chin, which was telling me: “Lift your head up.” He had a phrase: “Walk with the kings.” And he lived it. This was a man whose schooling had stopped in the sixth grade, and he had the intellect, the great vocabulary, of a doctor of philosophy.

The first time I really got to know Coach Lapchick was a significant moment in my coaching career. At another of those Metropolitan Coaches Association luncheons, as I was getting ready for my first season as a head coach, I asked him if I could sit down and talk with him sometime. He gave me his home address, which I’ve never forgotten: 3 Wendover Lane in Yonkers.

We hadn’t talked very long before he said: “What kind of training rules are you going to have?” “That’s one thing I wanted to talk to you about,” I said. What his recommendation amounted to was no training rules at all. I’m sure people would think I’d have a rigid set of rules kids would have to live by—be in by this time or that time, don’t do this, don’t do that. All those years as a coach, because of that evening I spent talking with Coach Lapchick, I had one training rule: If you do anything in any way, whenever or wherever, that I think is detrimental to the good of this basketball team, to the school, or to you yourself, I’ll handle it as I see fit. I think that was absolutely the best plan, and certainly he did. He told me why: “You’re going to have a kid who is a pain in the ass, and you’re going to be happy to get rid of him. And you’re going to have a good kid who screws something up. You can’t set down rules and then treat guys differently. You decide, based on your knowledge of the situation, what you’re trying to do with it, what’s best for the kid, and go from there.

His second question to me that night was: “How important is it to you that people like you?” I hadn’t thought about that. I did for just a minute or so and said, “I’d like to be respected as a coach, but I’m not concerned about being liked.” He said, “Good. If you worry about whether people like you or not, you can never make tough decisions correctly.”

I coached for eight seasons at West Point. In those years, I developed an interesting relationship with probably the three most prominent people in New York City basketball history—Clair Bee, Joe Lapchick, and Nat Holman.

When he retired in 1965, he was the most revered coach I had ever known, until I became acquainted with Henry Iba.

I took Coach Holman and Coach Bee to Mr. Lapchick’s wake. He had loaned me the scrapbook he had put together on the 1950s college basketball gambling scandal. He showed the scrapbook to every player who ever played for him after that happened. I gave it back to Mrs. Lapchick that night; several months later she sent it to me to keep. At the wake, she took me into a little side room and told me, “I know you didn’t play for Joe, but I want you to understand, you were one of his two favorites.” No comment ever meant more to me. And I never asked her about the other.

Every time one of my Army teams played in Madison Square Garden, when I would walk out on the floor I would look over to where he always sat. He’d put his thumb under his chin, which was telling me: “Lift your head up.” He had a phrase: “Walk with the kings.” And he lived it. This was a man whose schooling had stopped in the sixth grade, and he had the intellect, the great vocabulary, of a doctor of philosophy.

The first time I really got to know Coach Lapchick was a significant moment in my coaching career. At another of those Metropolitan Coaches Association luncheons, as I was getting ready for my first season as a head coach, I asked him if I could sit down and talk with him sometime. He gave me his home address, which I’ve never forgotten: 3 Wendover Lane in Yonkers.

We hadn’t talked very long before he said: “What kind of training rules are you going to have?” “That’s one thing I wanted to talk to you about,” I said. What his recommendation amounted to was no training rules at all. I’m sure people would think I’d have a rigid set of rules kids would have to live by—be in by this time or that time, don’t do this, don’t do that. All those years as a coach, because of that evening I spent talking with Coach Lapchick, I had one training rule: If you do anything in any way, whenever or wherever, that I think is detrimental to the good of this basketball team, to the school, or to you yourself, I’ll handle it as I see fit. I think that was absolutely the best plan, and certainly he did. He told me why: “You’re going to have a kid who is a pain in the ass, and you’re going to be happy to get rid of him. And you’re going to have a good kid who screws something up. You can’t set down rules and then treat guys differently. You decide, based on your knowledge of the situation, what you’re trying to do with it, what’s best for the kid, and go from there.

His second question to me that night was: “How important is it to you that people like you?” I hadn’t thought about that. I did for just a minute or so and said, “I’d like to be respected as a coach, but I’m not concerned about being liked.” He said, “Good. If you worry about whether people like you or not, you can never make tough decisions correctly.”

Last edited:

Rocket

Well-known member

He had the coaching temperament of Attila the Hun and I loved his military like discipline. I can tell you that the cadets at the point loved him and his greatest protégé coach K respected him unconditionally.

'The game has lost an icon': Bob Knight dies at 83

Bob Knight, whose Hall of Fame career was highlighted by three national titles at Indiana, has died at 83.www.espn.com

One of the alltime great coaches. You either loved him or hated him, or loved him and hated him.

I loved him but understand how others felt about him. Every 4 year player he had graduated. Old school tough in ways unacceptable now. Huge fan of our own Joe Lapchick, also Clair Bee and CCNY coach. RIP Coach

Oddly, two nights ago, I watched the 30 for 30, "Last days of Knight" documentary. I have strong opinions about the journalist that pursued the story that I won't share tonight.

My first college game at st john's feaured Army as the opponent with Bob Knight as coach. His point guard was a kid named Mike K-something who went on to win more than 1000 games as coach. The three men on the floor including our own coach C. Amassed 2500+ wins. Funny all 3 have direct or indirect ties to st. Johns.

I served with a 2nd lieutenant who played for him for three years and he stayed in contact with his coach after graduating.

blackpeter24

Well-known member

I attended a coaching clinic in which Coach Knight participated. He was the best.

Great clip and story! If I'd seen that one before, my advancing years had erased it from my memory...

Rest in Peace Coach Bob Knight. Up there with Wooden, Coach K, our own Coach Pitino on the Mt. Rushmore of modern (semi-modern in Wooden's case) College Basketball Coaches.

Heard him interviewed when he went into T.V. by a local young NYC reporter and he schooled the reporter on the history of St. John's BB, with great stories that exemplified his reverence towards Joe Lapchick, Lou C, and St. John's BB.

I worked with guys who were at West Point when he was there and to a man they respected him and really had nothing bad to say about him. Until years later and the incident in P.R. one of them -- (a former Special Forces with two tours of duty in 'Nam, and who got a masters in engineering from Michigan and got another masters from NYU much later in life)-- told me: "I can't believe some of Coach Knight's bad behavior it is not what I know about him."

Complicated man is an understatement but how can a SJU man not have a warm spot in his heart for someone who held our university in such high esteem.

[ I believe Coach Parcels coached West Point FB (linebackers) while Knight was there and they became friends; two peas in a pod].

Heard him interviewed when he went into T.V. by a local young NYC reporter and he schooled the reporter on the history of St. John's BB, with great stories that exemplified his reverence towards Joe Lapchick, Lou C, and St. John's BB.

I worked with guys who were at West Point when he was there and to a man they respected him and really had nothing bad to say about him. Until years later and the incident in P.R. one of them -- (a former Special Forces with two tours of duty in 'Nam, and who got a masters in engineering from Michigan and got another masters from NYU much later in life)-- told me: "I can't believe some of Coach Knight's bad behavior it is not what I know about him."

Complicated man is an understatement but how can a SJU man not have a warm spot in his heart for someone who held our university in such high esteem.

[ I believe Coach Parcels coached West Point FB (linebackers) while Knight was there and they became friends; two peas in a pod].

Both winners, similar temperaments, it's Knight's behavior that separates him from Parcels. No justification for that behavior no matter how many people have tried to excuse it away. I would want my kid playing for a man who coached like Knight, I would never have allowed my kid to play for a man who behaved like Knight. Treating other human beings like shit because you're in a position of power has never been my thing, but hey, to each his own.Rest in Peace Coach Bob Knight. Up there with Wooden, Coach K, our own Coach Pitino on the Mt. Rushmore of modern (semi-modern in Wooden's case) College Basketball Coaches.

Heard him interviewed when he went into T.V. by a local young NYC reporter and he schooled the reporter on the history of St. John's BB, with great stories that exemplified his reverence towards Joe Lapchick, Lou C, and St. John's BB.

I worked with guys who were at West Point when he was there and to a man they respected him and really had nothing bad to say about him. Until years later and the incident in P.R. one of them -- (a former Special Forces with two tours of duty in 'Nam, and who got a masters in engineering from Michigan and got another masters from NYU much later in life)-- told me: "I can't believe some of Coach Knight's bad behavior it is not what I know about him."

Complicated man is an understatement but how can a SJU man not have a warm spot in his heart for someone who held our university in such high esteem.

[ I believe Coach Parcels coached West Point FB (linebackers) while Knight was there and they became friends; two peas in a pod].

I bet Parcells was similar to Knight in coaching style (and I am a Giants fan who obviously loves Parcells). Difference is that Parcells did it to professional football players. (Have no idea how he was at West Point).Both winners, similar temperaments, it's Knight's behavior that separates him from Parcels. No justification for that behavior no matter how many people have tried to excuse it away. I would want my kid playing for a man who coached like Knight, I would never have allowed my kid to play for a man who behaved like Knight. Treating other human beings like shit because you're in a position of power has never been my thing, but hey, to each his own.

Phil Simms and Parcells famously yelled at each other on the sidelines, but they had endless respect for each other. College players could not get that type of latitude to express themselves.

Parcells was known to be belligerent and condescending like Knight. His behavior never got so out of hand as Knight's did. Both extremely demanding coaches.I bet Parcells was similar to Knight in coaching style (and I am a Giants fan who obviously loves Parcells). Difference is that Parcells did it to professional football players. (Have no idea how he was at West Point).

Phil Simms and Parcells famously yelled at each other on the sidelines, but they had endless respect for each other. College players could not get that type of latitude to express themselves.

In '84 Olympics Knight told Jordan you're the best player on this team so I am going to expect more out of you and I am going to get on you when you don't deserve it just to send a message to the rest of the team (Mullin second leading scorer on that team).

From what Beast quoted from Knight above, however, I do not think he would have put up with LT's antics like Parcells obviously did, even at the professional level.

I agree with the last part. That is why Knight never wanted to coach the pros.Parcells was known to be belligerent and condescending like Knight. His behavior never got so out of hand as Knight's did. Both extremely demanding coaches.

In '84 Olympics Knight told Jordan you're the best player on this team so I am going to expect more out of you and I am going to get on you when you don't deserve it just to send a message to the rest of the team (Mullin second leading scorer on that team).

From what Beast quoted from Knight above, however, I do not think he would have put up with LT's antics like Parcells obviously did, even at the professional level.

The great players like LT, who are a mess personally, are part of the pro job. Knight would have thrown chairs in his office just to blow off steam.

It's completely ironic that just 2 nights ago watched the 30 for 30 on Knight's fall from grace, entitled "The last days of Knight".

I completely understand anyone who wouldn't want to play for Knight or parents who wouldn't want their kids subjected to some of his outbursts.

However, Rick isn't exactly a marshmallow in practice or in games and anyone who denies that he is rough on players is in denial.

However, kids flocked to play for Knight and to Pitino because they know they make them better players. Both had long histories of nearly unparalleled success and sit at the top of all time greats.

Rick has stopped well short of the infamous PR chair toss, and to my knowledge never grabbed a player.

Honestly watched the 30 for 30 and in no way did Knight choke Neil but he had no business exploding and putting his hands on the kids throat even if it was less than 2 seconds. The kid disclosed it 2-3 years after it happened, then realized the intense blowback from Indiana fans was something he wanted no part of.

The incident that led to his firing was because he grabbed a student's arm who abrasively called out to Knight by his last name. Just about every IU student would know to address Knight as Coach Knight, Coach, or just plain Mr. Knight. Of course that inappropriately angered Knight who grabbed the kid's arm to admonish him sternly.

The author for SI was relentless in pursuing this story which ultimately brought down Knight. Neil Reed suffered tremendously as a result, nothing inflicted by Knight, but by how the story blew up and ended Knight's career at iu. Reed took no delight in that. He put on lots of weight, became a beloved school teacher but died tragically young from a heart attack.

Playing for Knight was not for every kid for sure. To me he had tons of redeeming qualities although admittedly that explosive temper wasnt one of them.

Still an all-time great of greats, a brilliant coach with more ethics in his finger than many have in their entirs bodies.

Finally a long time nyc hs coach once said to me about Knight, "You want to judge the man. Look at how long his assistants stayed with him. If he was what people say about him, they wouldn't have stuck around."

.

I completely understand anyone who wouldn't want to play for Knight or parents who wouldn't want their kids subjected to some of his outbursts.

However, Rick isn't exactly a marshmallow in practice or in games and anyone who denies that he is rough on players is in denial.

However, kids flocked to play for Knight and to Pitino because they know they make them better players. Both had long histories of nearly unparalleled success and sit at the top of all time greats.

Rick has stopped well short of the infamous PR chair toss, and to my knowledge never grabbed a player.

Honestly watched the 30 for 30 and in no way did Knight choke Neil but he had no business exploding and putting his hands on the kids throat even if it was less than 2 seconds. The kid disclosed it 2-3 years after it happened, then realized the intense blowback from Indiana fans was something he wanted no part of.

The incident that led to his firing was because he grabbed a student's arm who abrasively called out to Knight by his last name. Just about every IU student would know to address Knight as Coach Knight, Coach, or just plain Mr. Knight. Of course that inappropriately angered Knight who grabbed the kid's arm to admonish him sternly.

The author for SI was relentless in pursuing this story which ultimately brought down Knight. Neil Reed suffered tremendously as a result, nothing inflicted by Knight, but by how the story blew up and ended Knight's career at iu. Reed took no delight in that. He put on lots of weight, became a beloved school teacher but died tragically young from a heart attack.

Playing for Knight was not for every kid for sure. To me he had tons of redeeming qualities although admittedly that explosive temper wasnt one of them.

Still an all-time great of greats, a brilliant coach with more ethics in his finger than many have in their entirs bodies.

Finally a long time nyc hs coach once said to me about Knight, "You want to judge the man. Look at how long his assistants stayed with him. If he was what people say about him, they wouldn't have stuck around."

.

Last edited:

I wasn't so much talking about his barking at players during practice and games. K is notorious for that as well, as are many other great coaches. It's his well documented volatile behavior(my sense is that what we know is only the tip of the iceberg) both on and off the court. One well documented one was when a student called him "Knight" and he grabbed that student to lecture him on the concept of "respect". That's all good and well, except the concept of respecting others seemed to be lost on Knight most of the time. The first word that comes to mind when I think of him is "hypocrite". Would he allow his players and children speak to others the way he often did? Or have the kindI bet Parcells was similar to Knight in coaching style (and I am a Giants fan who obviously loves Parcells). Difference is that Parcells did it to professional football players. (Have no idea how he was at West Point).

Phil Simms and Parcells famously yelled at each other on the sidelines, but they had endless respect for each other. College players could not get that type of latitude to express themselves.

of physical temper tantrums the way he did? My guess, he wouldn't. So, like many powerful people, he felt like rules didn't apply to him. Except, at a certain point the chickens came home to roost and he got canned from his last 2 jobs because of his behavior.